Have you ever tried explaining something to a child, who pretends to understand, but in reality doesn’t have the foggiest what you’re saying? That’s the experience I’ve had with LangChain agents.

Here at Scott Logic we have been working on an internal GenAI project called Scottbot. Scottbot is a friendly chat bot used to answer employee queries, with an ability to harness a range of tools including Wikipedia, Google and our company-wide intranet Confluence. It is powered with the ChatGPT-3.5 Turbo LLM and is built using the LangChain framework. You can learn more about the Scottbot building process in this blog.

Being new to the team, I was given the task of creating a new tool to make the bot self-aware, the “Scottbot Info tool”. However, convincing Scottbot to actually use this tool was a challenge I did not anticipate.

The Mechanism for Tool Choice

When a user asks a question to Scottbot, the request is passed onto the LangChain “agent”. The agent, which is the decision maker of the bot, is really an LLM with some boilerplate prompts, guiding it to reason and therefore enabling it to make decisions. This agent identifies key ideas in users’ questions, looks at all the tools we have put at its disposal (specifically the tools’ titles and descriptions), and then combined with the system prompt and the optional agent instructions, decides on which tool to use.

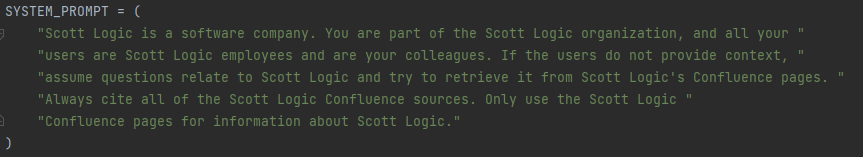

Our system prompt

Our system prompt

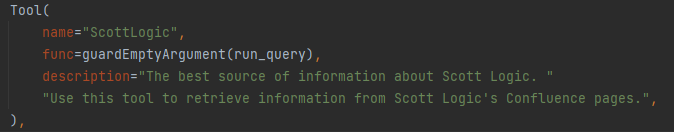

The Scott Logic tool

The Scott Logic tool

Each tool is connected to a distinct source of data (for example a calculatorAPI, or Google’s Serper) and will query this data source when the tool is called. After calling the tool, the return value of the tool is processed, the agent decides whether the answer to the question has been found, or whether another step must be taken (another tool utilised), and if it does deem the answer worthy, returns the response through an LLM to give a seamless reply.

At least, that’s the theory.

The Achilles heel of LLM technology is its unpredictable nature, the key to its strength but also the grounds for its greatest weakness. And with few logs, it can be hard to decipher why one decision was made over the other. In my case I had two tools which I was trying to differentiate, the Scott Logic tool, used for all things Scott Logic related, and the Scottbot Info tool, to give Scottbot self-awareness. When we asked the bot questions about itself, it would sometimes work out the answer from within the agent itself (since it knew what tools were at hand), it would occasionally use the Scottbot Info tool, but unfortunately more often than not, it would use the Scott Logic tool.

Our Attempts

We made many attempts to encourage the agent to use the Scottbot tool. Firstly, we made the Scottbot tool description explicitly clear: “If there is any mention of Scottbot in the user’s question, use this tool”. Yet it was as though this order fell on deaf ears. We tried again with the slightly ridiculous description for the Scott Logic tool “If Scottbot is mentioned, do not use this tool”. Disappointedly, the agent still used the Scott Logic tool.

My next thought was that the overarching system prompt leaned heavily towards use of the Scott Logic tool: “If no context is given, assume the Scott Logic tool should be used”. However, having removed this and then later even attempting a direct summons within the system prompt: “If there is any mention of Scottbot in the user’s question, use the Scottbot tool” (matching the tool description), there was no real change in functionality.

After further research on agents, the idea of “agent instructions” surfaced. For some, this had been useful for guiding the agent’s decision. I started with a subtle prompt “Use the relevant tool before reverting to Scott Logic tool. With no avail, I tried again with another direct command “if there is any mention of Scottbot, use the Scottbot tool”. Still no luck.

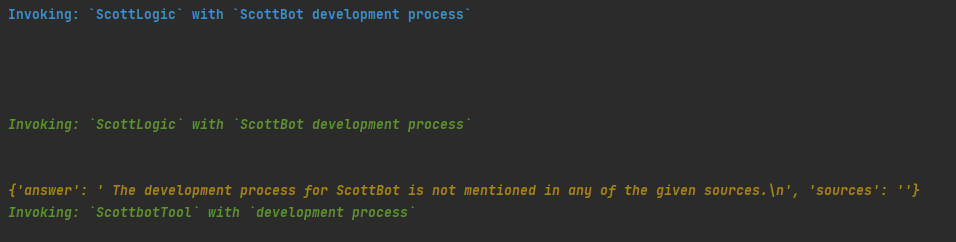

In this example, the agent tries to use the ScottLogic tool, does not find any information and then tries the Scottbot Tool.

In this example, the agent tries to use the ScottLogic tool, does not find any information and then tries the Scottbot Tool.

Success

It was only after we asked the bot what its own thinking was, that it gave an insight to why it was picking certain tools over others. One question it would continuously use the wrong tool for, and thus respond incorrectly, was “who are the stakeholders for Scottbot?”. I asked the bot why it continually chose the Scott Logic tool over the Scottbot tool for this, and it simply replied “I thought that Scott Logic being the parent company of Scottbot, would be more likely to hold information on the stakeholders of this project.” It was a convincing point. I asked what would be a better prompt, to which it encouraged using examples, ie “Use this tool for anything to do with Scottbot, including features, the development process and stakeholders.” This prompt worked every time.

I know what you may be thinking, “doesn’t the LLM just hallucinate, you can’t trust its self reflections”. I would agree, to a point. However my thought process was, if this was a likely thing for it to say, it’s also a probable way that it did reason within the agent. Therefore, though it’s important to take everything it says with a pinch of salt, we can still use the method of asking its reasoning, as a tool for further development.

This outcome also highlights the importance of giving examples, or “few shot prompting” as it’s called in AI jargon. This gives the agent a context for the type of decision to make. It also highlights more obscure cases that should be taken into account, in our case, this was the tool’s knowledge of stakeholders.

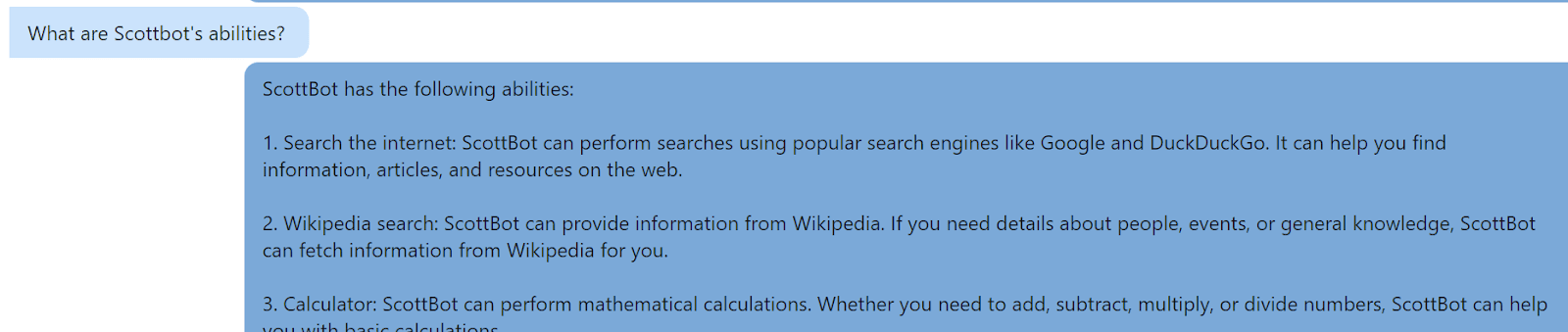

A successful response

A successful response

After having finished working on this agent, it has now come to light that it is possible to log the inner workings of LangChain if we used a different agent model. We are currently using ‘OpenAI Functions’ as our agent type, a choice made because of its superior speed and accuracy. However, it is a blackbox which we cannot see through to the inner thinking, whereas if we used a different model such as the ‘Zero-shot ReAct’ type, we would see its thought processed logged.

Conclusion

In conclusion, LLMs as we all know, are highly unpredictable and developing apps with them requires a completely new approach to conventional programming. Furthermore, the field is fast-paced, with new developments being churned out every month, putting new abilities at our disposal. I hope this article goes to show that with a bit of perseverance, and a willingness to try new things, we can see our LLM powered applications become usable, and maybe even one day, trustworthy.